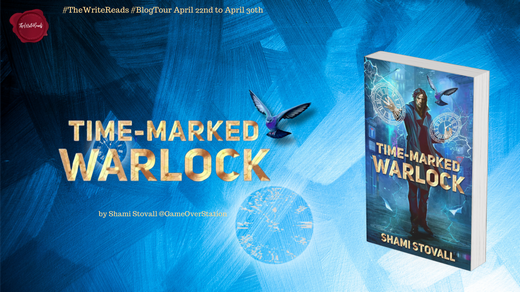

by Shami Stovall

DETAILS:

Series: Adair Finch, #1

Publication Date: June 2024 (or August, depending who you ask)

Format: e-ARC

Length: 402 pg.

Read Date: April 15-16, 2024

What’s Time-Marked Warlock About?

Until a few years ago, the names of warlocks Adair and Carter Finch were famous among the magic community. Private eyes who helped law enforcement as well as private clients dealing with cases large and small—they were pretty close to superheroes. Then they took that one job that put them against an opponent they weren’t ready for, things went wrong, and Carter died.

Adair’s magic couldn’t help. He couldn’t even track down everyone who was responsible, so he couldn’t get revenge. So…he went home and retreated from life. He became an asocial hermit, doing little more than existing.

Then one pre-dawn morning, a twelve-year-old girl pounds on his apartment door. Her mother always told her that if she was in real trouble to track down Adair or Carter Finch. They weren’t close friends by any means, but they did know each other—enough so that her name makes Finch pay attention. Bree’s mother was a witch and her father is a warlock, but not in the same league as Finch. Bree tells Finch that her mother has been murdered and her father kidnapped—and she needs his help to rescue her father and get justice for her mother.

Finch is not inclined to do anything but close the door on her face and get back to not interacting with anyone. But he can’t turn down her appeal—so he agrees to go to the crime scene (if only so he can determine that she misunderstood what she saw, and that her father actually was the murderer).

The scene isn’t what he expected—Bree might have been right. Also, the police detective on the scene knew Finch before he “retired” and neither really appreciated the other. Det. Jenner really rubs Finch the wrong way on the scene.

Between their less-than-pleasant interaction, Bree pulling on his heartstrings just right, and what Finch noticed at the scene of the crime, Finch decides to take the case, wrap it up quickly, and get back to wasting away as soon as he can.

Finch

Let’s get this out of the way real quick: Frequently reminded me of (James J.) Butcher’s Huntsman, Leslie Mayflower (and several other retired/depressed heroes, but Mayflower is most recent in my mind, so he gets name-dropped). Is he the Huntsman? No—he’s far less inclined to leave a trail of bodies in his wake.* for one thing. But he gives a similar vibe.

* We can argue some other time about how inclined Mayflower really is. Roll with it for now.

He’s clearly angry at himself. He’s reticent to put himself out there emotionally (or any other way). He’s not ready to let anyone else down again (assuming he really did). But something about Bree creates a crack in his defensive shell, and it’s great to see purpose emerge from where he’d trapped it down. He’s a different guy by the end of the book (probably like what he was years ago)—he’s not totally where he should be, but he’s on the road to recovery. As the series continues, i look forward to seeing how he grows/recovers.

Bree Blackstone

I don’t know how any UF reader is supposed to read her full name and not think of Harry Dresden. Maybe we’re supposed to—surely we are right?

Anyway…if Bree doesn’t melt your heart right off. If you’re not rooting for her to get the answers she seeks and maybe a touch of the retribution she longs for—and to save her dad…there’s something wrong with you—go listen to some Whos down in Whoville sing some Christmas songs until your heart is the right size.

She is so frightened by everything—there’s a real parallel to Finch there. But she’s determined to get the help she needs to save her dad and get the bad guy who killed her mom. And if Finch is the way to get both of those, she’ll get him to help her.

Naturally, along the way she picks up a pretty hefty case of hero-worship. Finch doesn’t see it for what it is right off—but he eventually does, and knows he’s not worthy. Watching him balance helping her, fending off (or trying to) her fangirling over him, and teaching her what she needs to know to be safe in the magic world is a great balancing act.

Bree is really well-conceived and executed by Stovall, and will become one of your favorite characters of the year.

Kullthantarrick the Sneak

Kull is a trickster spirit that Finch calls up to help with a little something along the way—she’s largely around for comic relief—but she also helps Bree to learn some things about the nature of magic, spirits, and the like that she hasn’t learned from her parents yet. Yes, her role is to help make worldbuilding infodumps entertaining. She’s well-used that way.

Any spirit of mischief—from Mercy Thompson’s Coyote to the Wizard in Rhyme’s Max to Al MacBharrais’s Buck, or…okay, I’m drawing a blank here—can be a lot of fun. You just set them loose to create havoc and sit back and watch. And Kull is great at that.

But that’s not all she is—she wants to be a human, she’s seen and done enough as a spirit, and she wants the human experience now. That adds a little depth to her—there’s also an affection that develops between her and Bree that adds even more shades of depth to what could’ve been a disposable character that ends up being so much more.

Really well done there.

The Magic System(s)

I don’t know how much to say here. This world has a handful of magic systems at play—there’s one for witches—like Bree’s mother and (presumably) her. There’s another one for warlocks—it’s similar and not necessarily mutually exclusive to the witch system. And there are some others, too.

One way that Finch uses his abilities (that other warlocks like Bree’s father can’t) is that he has some ability with time. It’s in the title, I feel I can give a vague description here. He’s constantly noting the time whenever anything happens. If he “marks” the time, within any 24-hour period he can return to the marked time—retaining the memories and knowledge gained, but getting to start over. Bree compares it to a save point in a video game.

This is brilliant—and so good to see in action. There’s part of me that wondered if it’d feel like a cheat—killing tension and so on. Or if it’d just be some Groundhog Day-riff good for comedy and that’s it. If you’ve ever played—or watched someone play—an intense video game with a save point, you know that’s not enough to keep someone from getting stressed out about almost dying/dying within the game. Sure they can take another try (or several), but the tension is still there. It works that way for this book (especially if it looks like Finch might not reset in time). And yes, there’s some weatherman Phil-esque humor, but not as much as other authors might have indulged in.

All in all, Stovall nailed this part of Urban Fantasy.

So, what did I think about Time-Marked Warlock?

Three great characters (not even counting the antagonists), an even better magic system, and a decent plot with a satisfying central villain. I don’t know what else to ask for in a UF novel.

The pacing was on-target—even when revisiting the same day or events over and over, Stovall was able to keep it fresh. She also knew when to say “they did X again” and when to show it. The action scenes worked well. The villain(s) were believable, had compelling motivations, and were enough of a threat to all involved to keep the reader’s interest.

There were supporting characters—including villain(s) that ended up not being as terrible as you might initially think—that were just as fully drawn, and you could generate a little sympathy for some of the people associated with the murder once you realized how they were being used, too.

There’s a good setup for further books in the series, too.

I really can’t think of much that Stovall could’ve done better—this scratched my UF itch, and I bet it’ll do the same for you, too. Keep your eyes peeled for the release and get your hands on this when you can.

My thanks to The Write Reads for the invitation to participate in this tour and the materials—including the ARC—they provided.

![]()