|

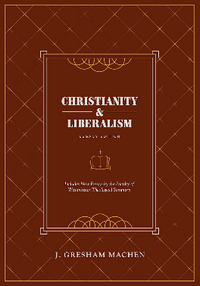

by J. Gresham Machen

Paperback, 266 pg.

Westminster Seminary Press, 2019

Read: October 20-27, 2019 |

Man…this is hard. Back in 1995, I heard a reference on a radio show to this book, and the hosts talked about how even though it was written over 50 years ago, it felt like it was written for the Church today. I figured I’d give it a whirl (not sure if I read it in 1995 or ’96, it was one of the two). I still remember being blown away by it, and wondering why I never heard anyone talk about it. I’ve since found myself in circles where people are familiar with it—but still not enough talk about it.

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve read this book. I know I’ve talked before about the author here, but not as much as I should/could have. Anyone who’s read what I’ve written about my son’s kidney transplant will have noticed that he was named after Machen. It’s because he’s a great writer, but it’s Who and what he writes about that makes me such a fan. Sure, he’s a fallen man, and has feet of clay (at the best of times), but he’s one we should all heed.

So clearly, there’s no illusion of a hint of objectivity to be found here.

Machen’s essential argument is this: Liberal Christianity is a different religion. It’s not the faith once handed down, it’s not that which was defined in the Ecumenical Creeds, it’s not that communicated by the Church Fathers, nor the Reformers, nor anyone else with a legitimate claim to Christian. It’s rank unbelief that isn’t honest enough to call it that. He’s clear—he wouldn’t waste as much time talking about them and their teaching if they’d just be honest about their goals, ends and beliefs. But as long as they persist in claiming they belong in the Church, he can’t do anything but oppose them.

Having set forth his thesis, he goes on to demonstrate it looking at the teachings of both Christianity and Liberalism as they are seen in the central areas of God and Man, The Bible, Christ, Salvation, and The Church. He doesn’t just lay out the problems of Liberalism, it’s not just a critique—he presents a positive case that the Bible teaches Christianity. While his criticisms still hold in Liberal Christianity (and can easily be applied to much of “Evangelicalism” today), it’s in his positive presentations where the text comes alive. The closing paragraphs of his chapter on The Church felt like they were written just for me (this time through the book anyway, other passages had that impact previously). For any part of a book to have that kind of impact after reading it (at least) a dozen times? That’s something special.

Machen has a tendency in his writing to lay things out in a pattern. My opponents say this thing over here, most of their critics say something over there, and all act like those are the two positions; but I propose to you a third way to look at the idea. But he doesn’t do that once in these pages. It’s very cut and dry—there are these men (theological liberals) teaching something they call Christianity, but it’s not it. On the other hand, there are actual Christians—yeah, there are important differences (and Machen has no problem identifying and discussing them), but on these issues we’re united. Unbelief vs. belief, period.

Each time I’ve read it, it feels fresh. Not like I’ve read it for the first time, but there’s something about his style that just jumps off the page. Yes, despite being 96 years old, it might as well have been published for the first time in 2019 (although the theological schools might have to get a new name). Clear, thoughtful, persuasive, it’s everything you should want (and get) in a book of this nature.

So aside from putting it out in a new, attractive cover, what’s the Legacy Edition have to offer? Seventeen brief essays about Machen, this book and how they live on in the work of Westminster Theological Seminary (which was founded by Machen and others as a result of the controversies addressed in this book which made it impossible to remain at Princeton Theological Seminary). This edition was produced both in the ninetieth year of the seminary and the first year that the book entered the public domain. So these essays commemorate both the book and the institution. My only complaint about them is the way that some shoehorned both the school and the book into the same essay, it just felt awkward. Most of the time that wasn’t a problem, but when it was . . . bleh. Other than that, these essays are helpful and good reading (some more than others, but none are bad). As I said, these essays are brief—I’ve written longer blog posts than some of them, so don’t let the number of them intimidate you. Also, it’s very possible to read the book and ignore them if that’s your thing.

This book has had such an impact on me and continues to do so, it’s really unfair to try to assign it stars. Five isn’t enough. The new essays are a nice little bonus, but it’s not like they improve on the classic, but they might help the reader appreciate what they read a little more. Get this edition, the older edition from P&R, or find an old, used copy. Just get it and read.

![]()