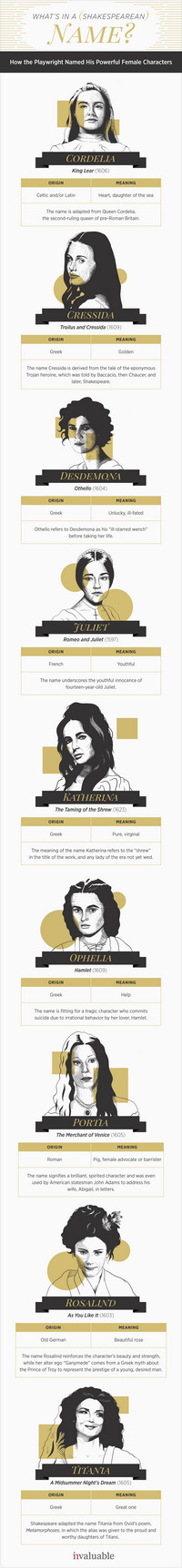

I’m very happy to have this guest post today — I just wish I’d set the schedule correctly. I love a nicely designed (and informative) infographic, and this definitely fits that. When I was asked if I’d be interested in posting this, I jumped on it. It’s a great way to commemorate the Bard’s birth.

—

April not only marks the start of warmer temperatures and a new pile of spring reads, it is also the month of the birth of legendary playwright, William Shakespeare. The writer was born on April 23, 1564, and to celebrate, we’re highlighting some of his most strong-willed female heroines. Invaluable created a neat visual [N.B.: the image is much nicer if you follow the link than it does on the left there] that showcases a handful of Shakespeare’s most influential female characters, and explains just how each of them was given their memorable names. From Ophelia to Juliet herself, browse through these wonderful female characters and relive some of the most electrifying plays written by the celebrated, William Shakespeare in honor of his birth.

April not only marks the start of warmer temperatures and a new pile of spring reads, it is also the month of the birth of legendary playwright, William Shakespeare. The writer was born on April 23, 1564, and to celebrate, we’re highlighting some of his most strong-willed female heroines. Invaluable created a neat visual [N.B.: the image is much nicer if you follow the link than it does on the left there] that showcases a handful of Shakespeare’s most influential female characters, and explains just how each of them was given their memorable names. From Ophelia to Juliet herself, browse through these wonderful female characters and relive some of the most electrifying plays written by the celebrated, William Shakespeare in honor of his birth.

Tag: Literature

The Magnificent Ambersons

The Magnificent Ambersons

by Booth Tarkington

Series: The Growth Trilogy, #2Mass Market Paperback, 346 pg.

Tor Classics, 2001 (first published 1918)

Read: May 12 – 14, 2016

… the grandeur of the Amberson family was instantly conspicuous as a permanent thing: it was impossible to doubt that the Ambersons were entrenched, in their nobility and riches, behind polished and glittering barriers which were as solid as they were brilliant, and would last.

If only, if only . . .

How do you enjoy a 300+ page book with a protagonist who is an arrogant, petulant, jackwad with no obviously redeeming qualities for the first 300 pages? Well, it’s tough. But if it’s as well told as The Magnificent Ambersons, it’s possible.

Sure, that’s a little bit of a spoiler — George Amberson Minafer does develop a couple of redeeming qualities in the last 30 pages or so. But you know what? The book is almost a century old, you’ve had plenty of time to read it if you’re worried about spoilers.

The plot is straightforward: At the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, an impossibly rich family produces an arrogant twit as the only heir. Unbeknownst to him, the economy is changing and the family is beginning to fall on hard times. Too proud to admit it, they continue living as if they have all the money in the world. Meanwhile, the twit falls for a girl who’s humble, kind, and wise. For some inexplicable reason, she falls for him, too. Things happen, they don’t get together and the bottom falls out on the Ambersons. There’s family drama, too — between the financial crisis, health problems, love, old flames, and scandal, there’s plenty to entertain a reader (if they can put up with younger George).

Most of the characters are pretty thin — there are exceptions (George’s mother, aunt and non-ambassador uncle, are the best) — but even the developed ones aren’t as fleshed out as we would have them today. But it fits with Tarkington’s overall style. It’s very, very difficult to like most of the people on these pages. So the ones you’d normally sort-of like, you end up really enjoying.

What makes this book work is Tarkington’s style. It’s hard to describe — highly detailed (for example, there’s so much attention paid to clothing and fashion that you’d almost think Gail Carriger had a hand in this), with a dry sense of humor, and plenty of cultural commentary. He changes his focus repeatedly: he’ll jusmp months or years at at time, and summarize events from those months in a paragraph or less and then cover a single evening in 15 pages, so he can highlight what matters and ignore the rest. But better than the plot (or characters), you get lines like this: “Some day the laws of glamour must be discovered, because they are so important that the world would be wiser now if Sir Isaac Newton had been hit on the head, not by an apple, but by a young lady.” How do you not keep reading for things like that?

Tarkington takes time out from the narrative to say

Youth cannot imagine romance apart from youth. That is why the roles of the heroes and heroines of plays are given by the managers to the most youthful actors they can find among the competent. Both middle-aged people and young people enjoy a play about young lovers; but only middle-aged people will tolerate a play about middle-aged lovers; young people will not come to see such a play, because, for them, middle-aged lovers are a joke–not a very funny one. Therefore, to bring both the middle-aged people and the young people into his house, the manager makes his romance as young as he can. Youth will indeed be served, and its profound instinct is to be not only scornfully amused but vaguely angered by middle-age romance.

I assume that captures the spirit of the late 19th/early 20th Century — if you take out the word “play” and put in “film” or “show,” it does a pretty good job of capturing the spirit of the early 21st Century, too. Which is a pretty nice achievement for a piece of writing.

The book isn’t a chronicle of the changes to the American culture/economy due to industrialization, it’s a family drama. But if you pay attention to what’s going around the lovebirds, cads and gossips, you can see those changes taking place. It’s a temptation for someone to cheat a little when writing historical fiction and make characters seem smarter than they are by knowing how predictions would actually turn out, Takington’s not above falling into that. Note what Eugene Morgan, early designer of automobiles says:

“With all their speed forward [automobiles] may be a step backward in civilization–that is, in spiritual civilization. It may be that they will not add to the beauty of the world, nor to the life of men’s souls. I am not sure. But automobiles have come, and they bring a greater change in our life than most of us suspect. They are here, and almost all outward things are going to be different because of what they bring. They are going to alter war, and they are going to alter peace. I think men’s minds are going to be changed in subtle ways because of automobiles; just how, though, I could hardly guess. But you can’t have the immense outward changes that they will cause without some inward ones, and it may be that George is right, and that the spiritual alteration will be bad for us. Perhaps, ten or twenty years from now, if we can see the inward change in men by that time, I shouldn’t be able to defend the gasoline engine, but would have to agree with him that automobiles ‘had no business to be invented.'”

That was 98 years ago, think what he’d say now about the automobile’s impact on culture (he’d probably cite James Howard Kunstler’s The Geography of Nowhere).

A dull(ish) story, full of unsympathetic characters acting foolishly (on the whole), with a quaint writing style that somehow makes it all work. I can’t explain it, I’m just glad I read it. You just might feel the same way, give it a shot.

—–

A Prayer for Owen Meany

A Prayer for Owen Meany

by John Irving

Hardcover, 543 pg.

William Morrow & Co., 1989

Read: March 4 – 10, 2016

[Marilyn Monroe] was just like our whole country — not quite young anymore, but not old either; a little breathless, very beautiful, maybe a little stupid, maybe a lot smarter than she seemed, and she was looking for something . . . She was never quite happy, she was always a little overweight. She was just like our whole country.

I’m not sure why I picked that quotation from this book, but there’s something that appealed to me about it (even if I don’t necessarily agree). You’ll note that there are both upper and lower case letters there — Owen Meany’s dialogue is always given to us in all caps. Which is annoying (it’s supposed to be), and difficult to read in extended speeches (Owen’s voice is hard to listen to), and makes you wish he’d shut up (duplicating the experience of most people who heard him).

A medical explanation for this is given, eventually. But the only explanation that Owen needs is that God gave him his voice. The same for his diminutive stature (about 5′ 0″ as an adult) — God made him that way, for His own reason.

But I’m getting ahead of myself — John Irving’s probably best known for The World According to Garp, which was one of the bigger disappointments of my college reading, so I wasn’t really looking forward to spending more time with him. You add in the fact that this is a 500+ page book with only nine chapters, and it’s downright intimidating. I’m not going to say that you shouldn’t be intimidated and that it’s a pretty easy read — it’s a challenge, it’s frequently a slog — but in the end, it’s rewarding.

When the book starts, Johnny Wheelwright (the narrator) doesn’t seem particularly fond of Owen Meany — in fact, you get the impression that he’s just one of those kids he happens to know, and he’s not that happy about it. But before long, it’s clear that he and Owen are really close — even though (because?) Owen’s responsible for the greatest tragedy of Johnny’s childhood.

John finds himself as an observer to Owen’s life, as his defender, his advocate, his way to the greater world. While Owen is constantly trying to help his friend — help him to achieve, help him to think, help him to believe. It’s a great friendship — and without the other, each was diminished. Owen less so, but in important ways.

The narrative is rambling — John starts to tell us about something, the plot moves forward a bit, but then he goes back in history to give context. Sometimes weeks, sometimes years and far more detail than you think is necessary. Eventually, you see that this is sort of the approach that the overall narrative is taking — John has something he needs to tell the reader, but he doesn’t want to. So he tells you many other things, anecdotes, vignettes, details you don’t need — anything to delay what he wants to say. He does get to it. And by that time, you’re not sure you want him to.

The story is told from the perspective of forty-something John, now a teacher at a Private School in Toronto — he spends his days reading the news about the United States, and ranting (or trying not to) to anyone near him about what President Reagan is doing. I’m not sure why we spend so much time dwelling on him in the present, we don’t need it — it adds almost nothing to the narrative. If anything, I think it might lessen the impact of the rest. The adult John telling the story about his childhood, about Owen, about their growing up together, and so on is essential — we need his perspective, his distance. What we don’t need is to hear John’s rants about Reagan, the poor reading/study habits of teenage girls.

I’m not sure that I get a whole lot of understanding of New Hampshire from this book — Owen’s family working in the granite industry doesn’t tell us much, New Hampshire is The Granite State — everyone who survived 4th grade knows that. If anything, Irving was wanting to talk about America — as an ideal, and as something that falls short of that ideal. Monroe was one example, John Kennedy’s moral failings another, Vietnam a recurring theme, and, of course, the Iran-Contra Scandal. Each of these, as either a representative individual, or representative act, demonstrates how far (in John’s/Owen’s view, at least) the United States has fallen short of the ideals it should strive for — if not achieve.

Ultimately, when I enjoyed this book, it felt like it was in spite of what I was reading. But I laughed, I cared, I kept reading — and then when I was finished, I appreciated the work as a whole, and felt a lot more affection for it than I expected. It’s hard to explain, but I liked this one and heartily recommend it.

—–

My Antonia

My Antonia

by Willa Cather

Author: Teri at Sportochick’s Musings

Blurb

Through Jim Burden’s endearing, smitten voice, we revisit the remarkable vicissitudes of immigrant life in the Nebraska heartland, with all its insistent bonds. Guiding the way are some of literature’s most beguiling characters: the Russian brothers plagued by memories of a fateful sleigh ride, Antonia’s desperately homesick father and self-indulgent mother, and the coy Lena Lingard. Holding the pastoral society’s heart, of course, is the bewitching, free-spirited Antonia.

Review

This story is narrated in first person by Jim Burden in what I think is a very plain unemotional manner. I honestly had a hard time reading this book and at points kept putting it down. It was puzzling to me that for all of the unusual dramatic events in this book it was for me unemotional. I am not sure if listening to it on Audible and switching off and on with the book impacted my feelings. Though these dramatic events in the book were described in fine detail my mind felt a distance from the writing.

Two characters did stand out. Antonia who was very expressive and Jim’s grandfather for the ways that he dealt with crisis’s, personality issues and his deep integrity. Antonia throughout the book was very emotional and it was obvious to see why quiet Jim liked to be around her and had grown to love her.

I finally connected with the book in the last chapter and a half where it became to me a book worth reading. This part of the book make me feel great sadness for Jim and Antonia and where they were 20 years later. The ending was poignant and still brings tears to my eyes.

This book leaves the readers pondering the what if. What if Jim didn’t go away to college? What if Antonia made a different decision when her first love deceived her? What if Jim had told her he loved her? But the largest question that I had was how did Jim love Antonia? A sister, friend, lover? This book left me feeling sad because if Jim had more gumption his life would of been so different than it was. It also left me pondering on how many people lost out on the best thing of their lives because they were afraid.

The Prince of Tides

The Prince of Tides

by Pat Conroy

Hardcover, 567 pg.

Houghton Mifflin Company, 1986

The story of the Wingos is one of humor, grotesquerie, and tragedy. Tragedy predominates.

So warns Tom Wingo before beginning to relate that story to Dr. Susan Lowenstein. Lowenstein is Tom’s sister’s therapist and needs his help to understand Savannah, who recently tried to kill herself for at least the third time. Savannah’s now institutionalized until she gets back to a place where she can handle her PTSD (my diagnosis, not Lowenstein’s), psychosis, and whatever else they diagnose her with.

As he has done before, Tom has dropped everything and rushed to New York City (from the tiny community of Colleton, South Carolina) to help his sister. The best way to do that, Lowenstein says, is to fill in the large blanks of memory that Savannah demonstrates. Then, she’ll be able to help Savannah remember and move on from whatever trauma has brought her to this stage. Tom agrees — not only has he come to help his sister, he’s also taking a break from home: he’s been unemployed for a year, he just learned his wife is having an affair and might leave him — maybe by helping his sister’s therapist help her, he might get help in the process.

Before he gets the call about his sister and finds out about his wife, Tom’s spending time with his three daughters and jokes with them:

. . .parents were put on earth for the sole purpose of making their children miserable. It’s one of God’s most important laws. Now listen to me. Your job is to make me and Mama believe that you’re doing and thinking everything we want you to. But you’re really not. You’re thinking you own thoughts and going out on secret missions. Because Mama and I are screwing you up. . . I know we’re screwing you up a little bit every day. If we knew how we were doing it, we’d stop. We wouldn’t do it ever again because we adore you. But we’re parents and we can’t help it. It’s our job to screw you up.

That’s not the last time Tom will joke about this, but he’ll spend far more time showing and telling the reader about how parents go about screwing up their kids — he, Savannah and their older brother, Luke, are proof of that (there are four exceptions to this in the novel — but I can’t help but think that with some more investigation, they’d be shown as screwed up, too).

The seeds of this parental function are planted on the night of the twin’s birth, and soon flower while the children are (at least) toddlers — and it doesn’t stop, ever. To detail it would be to give too much away, but Tom, Savannah, and Luke have horrible childhoods and the proof of that is writ large all over their adulthood. Which doesn’t mean that the book is entirely grim — their father has bouts of generosity, of letting his imagination get away from him and getting the family involved in an escapade; they have loving grandparents; they’re successful at school (in differing ways); they adore their mother (rightly or wrongly); they have adventures — they’re actually happy frequently. But then the reality of their poverty, their abusive father, their (I’ll let you fill in the blank if you read it) mother, will revisit them and things will be grim again. Early on, we’re told that something horrible happens to Luke just a couple of years before this most recent suicide attempt, their father is in jail, and that his mother has remarried (to someone Tom hates more than his father). Slowly but inexorably, we march toward those ends. Alternating with the tales of their past, we see Tom in New York, trying to help and understand his sister, as well as the growing friendship between Tom and Lowenstein.

At the end of the day, Lowenstein’s son is the only character that I liked (and maybe Tom’s daughters — but we spend less than ten pages with them, so it’s hard to say). Which doesn’t say a whole lot for the rest of this motley collection of scofflaws, narcissists, manipulators, bullies and gulls. Thankfully, you don’t have to like all the characters to appreciate a well-written, well-structured novel. Which this largely is.

I’m not entirely convinced it’s as good as it thinks it is, however (it, and most readers, it appears). It frequently seems over-written — too much squeezed into a sentence; sentences filled with sesquipedalian words (after paragraphs without any); the humor seems forced sometimes; the dialogue is frequently stilted. The flashback segments appear to be what Tom’s relating to Lowenstein — but I have to wonder if they’re more detailed for the reader than they are for Lowenstein. She complains that Tom’s not forthcoming about the mother (unless maybe his version conflicts with what Savannah has been telling her), because I think I get a pretty clear picture of her from that.

There are some reveals promised early that Conroy doesn’t deliver until towards the end — and he mostly delivers well. However, one of the big reveals (at least Conroy played it as one), was telegraphed so clearly hundreds of pages before I didn’t think it even needed to be mentioned — it could just be assumed. Like he didn’t need to mention that the football coach from South Carolina had an accent. Telegraphing it the way he did made it seem like an authorial or editorial failure. There was one reveal that was promised only a chapter or so before we got it — I’m glad I didn’t have to wait long for it, because of all the things he teased, this was the most vital (and most disturbing) — setting up Savannah’s first suicide attempt and the rest of her life (it seems).

I’m sure I’m in the minority here, but I think the book tries to do too much — especially by the time it gets to the end, where Tom is beginning to tell us the dark thing it’s been hinting at about Luke, the set-up for what happens to Luke was just too much. Conroy covers race, regionalism, psychiatry, feminism, theories of masculinity, how sports can be noble, spousal/parental abuse, marital fidelity, marital love, marital betrayal, sexual assault, school integration post Brown vs. Board of Ed, Vietnam, property rights, the drug war, quixotic faceoffs against the federal government . . . and other things I’m forgetting. It’s just too much — especially to befall one family (even if three generations are in view).

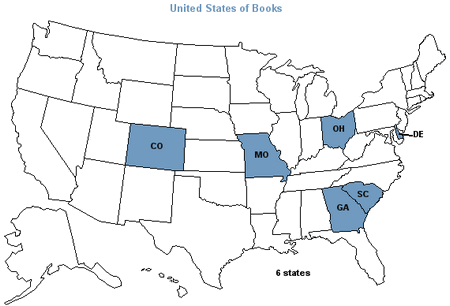

So as part of this United States of Books series, one thing I want to look at is why the book was chosen, what did the novel teach me about the state, why did EW pick it as “the one work of fiction that best defines” South Carolina? It’s definitely not because it paints the residents in the kindest light — the constant contrast between small-town SC versus a fairly idealized New York City (or at least affluent NYC) doesn’t do the state any favors. There’s a sense of a mix of pride and shame about the people, the history, and legacy of the state. The sharp class distinction — not just racial — drove so much of the characters actions and desires that it seems to be part of their DNA (although it can be overcome with the right strategy and dedication). It’s not the best part of the country to live in, the book seems to say, but those who embrace the life, the state, develop a great love that transcends all sorts of regional, intellectual or philosophical chauvinism. Also, I should’ve realized, but didn’t, that there was more to SC coastal industry than tourism, never occurred to me that there might be shrimpers, lobster trappers, etc.

“There’s a difference between life and art, Savannah,” I said as we moved out into the Charleston Harbor.

“You’re wrong,” she said. “You’ve always been wrong about that.”

I knew very little about this book going in. I remembered when I was in college shortly after the movie came out that everyone talked about Conroy as if he were a genius. I knew that the movie (and therefore, probably the book) involved some rough-and-tumble guy and a classy psychologist in therapy (and in bed, based on the movie poster). I’ve seen Conroy interviewed and in documentaries, I knew he considered himself a “Southern Writer” in the tradition of Faulkner, Harper Lee, Flannery O’Connor and James Dickey (his influence is clearly seen). But beyond that, I didn’t know what to expect. I think maybe more than this. I have to give this a mixed review — there’s a lot to admire here, scope, character, the way he told a multi-layered story about very familiar subjects in a way that (mostly) didn’t seem to tired or cliché. But, oh, I spent a lot of time hating this book. There were at least two times, maybe three, that I almost walked away from this — and I probably would have if it wasn’t part of this series. I’m not entirely sure that I’m glad I finished.

I’d love to read what you all have to say about this — fill up this comment section! Convince me that I was wrong about this work of genius (or, that I was right to have misgivings).

—–

Mixed Rating:

Did I like it?

Did I think it was well-done? (lost a 1/2 star in the last 50 pages or so)

Gone with the Wind

Gone with the Wind

Author: Elisha at Rainy Day Reviews

Entertainment Weekly says – Mitchell’s landmark novel illustrates the luxury of the Southern antebellum aristocracy and its downfall through some of literature’s (and film’s) most memorable characters.

Gone with the Wind Review

Gone with the Wind is a classic for a reason. Well written, timeless, and tells a story of bravery, heart, and the difficulty of living life during the Civil War. I can see why people would call this novel a romance however, I would not call this a romantic read but a dramatic read with romance as a key part of the novel. Even though I was not a big fan of Scarlett, she had backbone and had to learn rather quickly that life was not always as easy or pleasant as she once thought due to the civil war and the surrounding issues of life then on the plantation. All around a great book and I can see why the movie is four hours long and look forward to watching it (I still haven’t seen it).

I most definitely would recommend this read for all.

Synopsis

Since its original publication in 1936, Gone with the Wind —winner of the Pulitzer Prize and one of the bestselling novels of all time—has been heralded by readers everywhere as The Great American Novel.

Widely considered The Great American Novel, and often remembered for its epic film version, Gone with the Wind explores the depth of human passions with an intensity as bold as its setting in the red hills of Georgia. A superb piece of storytelling, it vividly depicts the drama of the Civil War and Reconstruction.

This is the tale of Scarlett O’Hara, the spoiled, manipulative daughter of a wealthy plantation owner, who arrives at young womanhood just in time to see the Civil War forever change her way of life. A sweeping story of tangled passion and courage, in the pages of Gone with the Wind, Margaret Mitchell brings to life the unforgettable characters that have captured readers for over seventy years.

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

by Mark Twain

Author: Laura at http://125pages.com

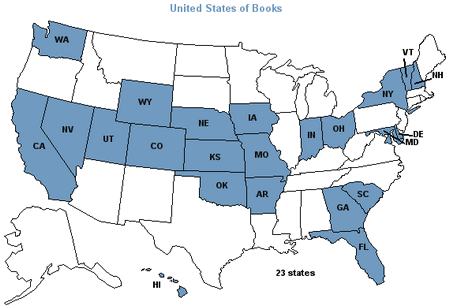

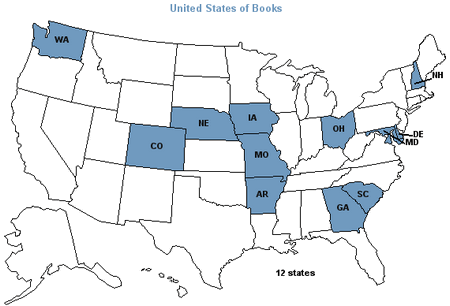

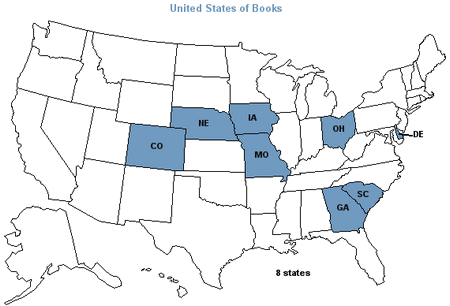

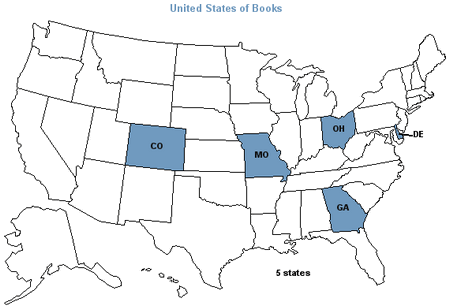

Welcome to another installment of the United States of Books! See full details here. Today we will visit Missouri with The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain. Entertainment Weekly says “Twain’s masterpiece about Missouri’s most iconic literary contribution, Huck Finn, will resonate for as long as America’s rivers flow.”

I’m not sure how I never read The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn before now. I read The Adventures of Tom Sawyer in high school and upon looking on my shelves I discovered I already owned both of them. Finn takes place soon after the events of Sawyer, with both boys wealthy and Finn living with the Widow Davis as his alcoholic father has not been seen in a year. Stifling under the rules, Finn seeks adventure. He rejoices when he is able to sneak past Jim, a slave who keeps watch over the house, to join his friends as they play robbers at night. When his Pap finds out about his windfall, he returns to town seeking the money. He kidnaps Huck and locks him in an isolated cabin. Huck the stages his own death to escape and sets off down the river. He happens upon Jim, who is also running after hearing about plans that he is to be sold. A series of madcap adventures follow, including grifters pretending to be royalty, cross-dressing, family feuds and an elaborate plan to save Jim.

This was a hard book to rate as it is not on the same level as current books. The six distinct dialects used made it not flow as modern literature does, but added a unique aspect to each word said. The writing was humorous and full of heart. Yes, at times, the words used do not match what we consider proper, but for the time it is accurate. The plot was all over the place, but always made its way back to Huck at the center. The pacing was quick and the story never lagged.

A true classic in terms of setting, language and speech patterns, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, is a unique look at a not so shiny time in our country’s past. That being said, the correlation between Huck running from what he considered slavery, and an actual slave running with him for real freedom was powerful. Seen from a child’s eyes, what was normal became unthinkable, as Huck learned to count on Jim. Mark Twain crafted a nuanced picture of such a specific time frame, I think The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn will never not be read by those seeking to understand the past.

Favorite lines – It was kind of solemn, drifting down the big, still river, laying on our backs looking up at the stars, and we didn’t ever feel like talking loud, and it warn’t often that we laughed—only a little kind of a low chuckle. We had mighty good weather as a general thing, and nothing ever happened to us at all—that night, nor the next, nor the next.

Biggest cliché – “Running away will be super easy and fun.”

Have you read The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, or added it to your TBR?

—–