The last book I’ll look at for #IndieCrimeCrawl (not my last post for the Crawl) is the latest from Helen Fitzgerald. Unlike the others I’ve blogged about this week, Fitzgerald is a new author to me, and the only thing I know about her is that a few weeks ago, about half of my bookish twitter feed was full of people praising this book. I don’t remember who is the one that convinced me I should pick up this book — I could pretty much pick a name at random and come up with a decent candidate though. I don’t see anyone but an independent publisher allowing this story to be told in the way it is. I think many publishers would take a version of this novel — a restrained and somewhat neutered version of it, sure — but not this version. This protagonist, this story, this author and this publisher are textbook examples of the strengths of Independent Crime Fiction. Without further ado:

—

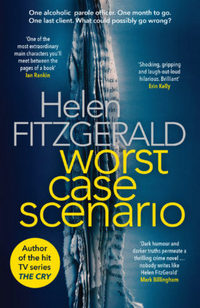

Worst Case Scenario

Worst Case Scenario

by Helen Fitzgerald

Paperback, 207 pg.

Orenda Books, 2019

Read: July 13 – 15, 2019

| When Mary decided to get her diploma [to become a Social Worker], she believed it would be her role to stand on bridges and stop people jumping off. Very soon after qualifying she realised she would never stand on bridges. She and everyone else were too busy catching casualties downstream. Except for sex offenders. If you saw a drowning sex offender being swept with the current you threw a large rock at him. Mary had done her best work in her first five years in the job. Those early cases were the ones she could recall, where she’d made the time and had an impact. She should have been forced to resign at the five-year mark. Every worker should. |

| Please let me get through today without killing a child, they’d all be thinking, as Mary had thought for the last thirty years. Please help me not ruin a child’s life. She’d prayed each day that she’d get through it without fucking up, without turning out to be the bad guy after all. No-one in the office was expecting fame, riches, or even thanks, even though each worker would have made an excellent protagonist in It’s a Wonderful Life. They all saved lives, all the time, but no-one ever noticed. Boy did people notice when it went wrong, though. |

Mary Shields is a social worker/probation officer, and I can’t imagine that there are many in either field that can’t recognize themselves a little in those above quotations (I couldn’t pick one). It’s probably my (understandable) lack of knowledge about Scottish penology/jurisprudence, but I don’t get exactly how her job works. She refers to herself as a social worker, and seems to work for a private employer, while she manages people on probation. It didn’t impact the novel for me, it’s just something I stumbled over a few times.

Before I go on, can I just ask something? Police procedurals and PI novels are never going away, but are we done with Forensic Scientists/CSI-types now and moving on to Probation/Parole Officers? Maybe it’s just me, but I’ve gone my entire life without reading a book focused on/featuring a Probation Officer and now I’ve read two in the last month and a half. I’m all for it, if the books are as good as these two are, I should stress.

Anyway, Mary is going through several changes in her life — including The Change. Her adult son has finished school and has found gainful enough employment that he has moved into his own place, her husband—a struggling artist for years is on the brink of making good, reliable money; and her own employment is getting the best of her—the schedule, the clients, the management—it’s all too much and with Roddie about to have a reliable income, she’s decided to give her notice once things become official for him. Having made that decision, she’s being a little less careful than she should be with her clients. Instead of doing everything by the book and diplomatically, she’s going to cut to the chase and do what she can to protect society from her clients and do what’s right for the people around them (even if they don’t want her to.)

The strategy sounds all well and good, but the execution could use a little work. Mary describes her role to one client as imagining the worst case scenario and then working to make sure it doesn’t happen. Well, she couldn’t imagine this scenario if she’d tried. Things start to go wrong immediately, and to a degree she can’t cope with.

The biggest example of this (but far from the only) is Liam Macdowall, her newest client. He was convicted of murdering his wife, and is on the verge of release. Not at all coincidentally, on the same day, his book is due to be published. It’s a series of letters he wrote to his dead wife from prison, essentially exonerating himself and putting the blame for the problems on his life on her. He’s become the poster child for Men’s Rights Activists throughout the country and his release is the occasion for protests (not necessarily the non-violent kind) for feminist groups as well as his fellow MRAs. Mary lays down the law on the eve of his release, setting forth very strict guidelines and expectations for him. Which is begins openly defying within hours of his release.

Before Mary can do anything about it, thing after thing after thing go disastrously wrong—regarding Macdowall, but with other clients, too. I can’t get into the details, but let’s just say the best of the things that go wrong is that her own son begins dating Macdowall’s oddly devoted daughter and sipping the MRA Kool-Aid. Everything that Mary tries to do to either fix the problems in her life, or just alleviate them, fails miserably. The only thing thing that doesn’t blow up in her face is retreating home to her bed and streaming Sex and the City. Her life doesn’t go from bad to worse just once or twice, but at every turn, she finds another level of worse for things to go to.

I’ve never talked about Christopher Buckley on this site, which is a crying shame (if only because I’d like to link to the posts demonstrate this point), but I haven’t read anything by him since I started here. I’ve been reading him since the late Eighties and love his approach to satire. The problem with all of his novels (with one exception) is that the last 5-10% seems to get away from him—like a fully-loaded shopping cart speeding down a hill. No brakes and only gravity and momentum exercising any control over what happens to it, while the wheels are close to falling off. I mention this only because I kept thinking of Buckley’s endings while reading this. There are two significant differences—the out-of-control part set in around the 25% mark and somehow (I wish I could understand how) Fitzgerald pulled it off. I do think in the last 15 pages or so, the wheels got a little wobbly, but while things felt out-of-control, Fitzgerald kept things going exactly where she intended.

While I don’t understand fully how Fitzgerald kept things from spiraling out of control in the novel (not Mary’s life) is the character of Mary Shields. She’s just fantastic. She’s funny (usually unintentionally); earnest but jaded; angry at so much of what’s going on around her; fully aware that she’s a mess (and not getting better); yet she pushes on in her Sisyphean tasks to the best of her ability. Her life is a car wreck, and we are invited to rubberneck as we drive by. When we read:

| …she didn’t want to kill [Macdowall’s MRA publisher], as this would mean losing the moral high ground. |

we actually understand her frame of mind. She’s a woman whose life is crumbling around her and she’s doing all she can to hold it together for just a few more days until she can retire.

We don’t get to spend enough time with other characters to get a strong sense of them—this is all about Mary and the disaster that is her professional, personal, and family life. I liked the portrayal of almost everyone else in the book, I just wish the style of the novel allowed Fitzgerald to develop them more fully. Particularly the MRAs—I felt that their depiction was rather shallow and lacked nuance, making them rather cartoon-y. Sure, you could argue that she’s just being accurate and MRAs are cartoon-y, but I’d like to see a bit more subtlety in their portrayal. But on the whole, things are moving so fast, and Mary bounces from one calamity to another so rapidly that there’s no time to develop anyone else.

There’s a lot about this book that I’m not sure about, and a significant part of me wants to rate it lower. But I can’t largely because of Mary Shields. I’ve never read anything or anyone like her. This is definitely a Gestalt kind of novel—various parts of it may not make a lot of sense; or may be good, but not great. But the whole of the novel is definitely greater than the sum of its parts—when you take all the parts that may not be that stellar and combine them the way that Fitzgerald did—and with Mary at the core—it works, it all really works.

Insane, fun, insanely fun—and probably a little closer to reality than any one is ready to admit. I have a number of family members and friends in the social work/probation/parole fields—and I’m probably going to insist that most of them read this while I encourage all of you to do the same. I can virtually promise that you won’t read anything like this anytime soon.

—–

1 Pingback