|

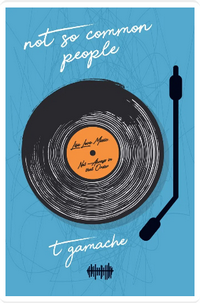

Not-So-Common Peopleby T Gamache Paperback, 209 pg. Read: November 27-28, 2019 |

” . . . I don’t want to surprise you.”

Surprise me, hell I’m Captain Blindside lately! Every time I turn around one of my siblings is tossing a proverbial bombshell in my direction. I’m barely keeping this crap together, Calvin! When did it become a good idea to throw your emotions at Nathan? I’ll tell you when, NEVER! I’m the introverted, quiet, keep to myself guy in the family. Not the “hey, here’s our crazy laundry” guy!

Nate is a self-professed music geek/snob. That’s his primary description. He’s also a hipster barista with control issues (which he keeps hidden most of the time). He’s around thirty now and should really be making an effort to do something with his life/college degree rather than work part-time at a coffee house. This novel isn’t so much a coming-of-age novel about Nate, as it is that external forces impose age/maturity upon Nate. Which is a great and novel way to approach this kind of character.

I was trying to come up with something to say about the other characters in the novel, and realized that I really didn’t get enough of any of them, except maybe Rick and his parents. I do think they’re probably well-developed and three-dimensional, but there’s so many of them (including people who are maybe around for one scene—like various co-workers) that they can come across as flat and two-dimensional just because we don’t get to spend that much time with them.

For starters, we’ve got Claire, the BFF and roommate—always good for emotional support and sage advice; Frank, his other roommate; Gary, Frank’s fiancé; and Rick, the proprietor of Nate’s record shop—a frenemy of sorts. There’s Nate’s parents and then his siblings—Graham, the Type-A businessman; Calvin, the Lutheran minister; and Marcie, a housewife and mother. Last, but not least, we have the object of his affections, Anne, a little quirky, a little geeky, and driven to succeed.

In the weeks following a fateful Thanksgiving, each of his siblings goes through a major life-changing event (or series of events). And for reasons that he cannot understand, they turn to Nate. Not only do they turn to him, he steps up to help (which might surprise him more than the fact that they came to him for support). Sure, he doesn’t always know what to do for them (this is where Claire and Frank come in), but he’s willing.

In the middle of all this induced maturing, Nate meets Anne. Who is charming, attractive, and funny. Nate falls for her—probably in a ridiculous way—in a time when that’s the last thing he has time for.

While his siblings are reeling and he’s twitterpated, Nate realizes that his life needs some less dramatic life-changing, too.

We really need more time with Anne—it’s hard to buy how involved he gets given their time together (but, it’s cute and you do want to root for them to have a Happily Ever After). And it would be good for us to get more time with the siblings and roommates, too—they all need a little more space.

I have issues with Calvin being a Lutheran minister. If he was some sort of Methodist or non-denominational minister, I’d buy it. But he doesn’t seem that Lutheran to me (he’s definitely not a Missouri Synod or Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran; and he’s not believable as a ELCA minister, either—but that’s closer). I definitely am uncomfortable with the way his religious activities are portrayed, but I can understand why an author would characterize them in the way that Gamache does.

This is a sweet story, a touching story, with a very likable protagonist (even if he wouldn’t believe me saying that), and you can’t help but want to cheer all these characters through their lives being upturned. If my biggest complaint is that we don’t spend enough time with the characters, I think that’s a pretty decent compliment. Recommended.

Disclaimer: I received a copy of this book from the author in exchange for my honest opinion. I appreciate getting the book, but not so much that I altered my opinion.

This post contains an affiliate link. If you purchase from it, I will get a small commission at no additional cost to you. As always, opinions are my own.

![]()