by Michael Landweber

Kindle Edition, 208 pg.

Coffeetown Press, 2016

Read: May 18 – 19, 2016

Towel Day is tomorrow, so it seems apropos to start with a couple of Douglas Adams lines that I’d imagine Duck quoted to himself, assuming he read the book: “This must be Thursday . . .I never could get the hang of Thursdays.” and “Time is an illusion. Lunchtime doubly so.” Now, if anyone could empathize with Arthur and Ford, it’s Duck.

Towel Day is tomorrow, so it seems apropos to start with a couple of Douglas Adams lines that I’d imagine Duck quoted to himself, assuming he read the book: “This must be Thursday . . .I never could get the hang of Thursdays.” and “Time is an illusion. Lunchtime doubly so.” Now, if anyone could empathize with Arthur and Ford, it’s Duck.

(like I need an excuse to quote Adams, really, but I’ll take one)

And you never know, maybe he had read Adams, after all:

We’d read Fight Club in Mr. Lorenzo’s Anarchy in Modern American Fiction class . . . And Lord of the Rings in Ms. Tutwell’s Geography of Fictional Lands seminar, which somehow got me Social Studies credit. Damn, I went to a really questionable high school.

So, earlier today, I posted something from the publisher with the idea behind this one. Basically, Duck’s head is nowhere near where it should be as he walks the busy streets of D. C. and he steps out in front of a car that doesn’t hit him. Not because of lightning-fast reflexes of the driver, nor because of fantastic brakes, or because some hero pulled/pushed/tackled him out of the way. Nope, none of those — but because faster than you can say “Rod Serling,” time stopped.

Now our 17-year-old protagonist has to figure out: what happened (if he can); how to survive in this Frozen World (if he can); and most importantly — how can he get things moving again (if he can).

Simple enough premise, right? Yup. One that seems like you’ve probably read/seen it a few times (seems that way, but I can’t remember once) — but Landweber executes it like he’s the first. It feels fresh, new and innovative — while being an old stand-by, figure out how he pulled that off and I’ll probably end up talking about your book, too.

As we talked about a little while ago, there are very strict rules governing this reality and Duck figures them out pretty fast (at least fast enough to survive awhile).

Now seems like a good place to explain what people feel like in the frozen world. Skin feels like skin, hair like hair, lips like lips. It’s one of those things that is almost normal. When no one moves, you expect them to feel like molded plastic, like mannequins, limbs swiveling on set pivots without much range. A secondary possibility was that everyone would feel rubbery, like the well-preserved fetal pig [Duck’s friend] Grace dissected for me. Wrong on both counts.

The inert water hung down from the showerhead like strands of silk caressing his body. I touched one and it came away from its cohorts, wet and liquid on my fingertips.

And, yes, that sounds kind of creepy going around touching skin, hair, lips, some dude’s shower water — but don’t worry, that’s only because it is creepy. And Duck would be the first to admit that (probably while blushing). One reason I liked the paragraphs I quoted was because, yeah, molded plastic is exactly how I’d have figured it to feel.

Duck composing a “Guidebook” to how to live in this kind of reality ticks off a few boxes: lets us see his personality, lets him talk about his experimentation to discover the rules in a slightly more objective way than the rest of his narration, and lets him give the readers an info dump — several, actually — without it feeling like one. A very nice move there.

Landweber gives us a few details a little at a time about this reality, what Duck’s been going through in the days/weeks/months leading up to stepping in front of the car (like where that nickname comes from — a tale that’s both tragic and funny). As little as he’s been paying attention to the outside world, it might as well have stopped. So one of the things he does during this time is figure out what’s been going on with his friends — between family crisis and adolescent male hormones, he’s missed a lot. He just hopes that he can make up for this time.

For the most part, this book comes across as light entertainment — but there are (at least) two big dramatic stories at play here in addition to the fun and games. There’s death, the nature of love (and reality of lust, teenage style), growing up, friendship, hurting others . . . and Duck coming to grips with all of these, and coping with them isn’t done in a heavy-handed, or overly serious manner. On the whole, while you’re chuckling about something he’ll slide right into a consideration of one of the heavier themes. Over and over again, Landweber does this seamlessly so you barely notice it. No mean trick to pull off.

In addition to that, Duck deals with some pretty deep ethical questions (and doesn’t always come up with the right answer). His father, a philosopher, had posited that:

there is no good or evil without time. Empirically, he argued, man’s actions in themselves are not right or wrong. It is only the interaction of those deeds with the passage of time and the judgments of others that leads to morality. If you were to freeze time at the instant of the act, and never allow for there to be recriminations or regret or accusations or revenge, then the act itself becomes a meaningless one. No matter what that act is. Merely a moment detached from all other moments. A moment without consequence.

Duck’s got more than enough of these detached moments, moments without consequences, to deal with. And watching him deal with these ideas and try to be moral (frequently) is a really nice touch that I don’t think I expected from the premise.

It’s told in a light tone — and never gets spooky or too tense, but that doesn’t stop what Duck is dealing with from being serious — and dealt with seriously (much of the time). Landweber balances that pretty well most of the time — while keeping Duck as believable as possible in this situation. It is a compelling read, a fun read, and a moving read. Breezy enough to keep the YA crowd engaged, and thoughtful enough to make it worthwhile.

You really want to go get your hands on this one, readers, you’ll enjoy it.

Disclaimer: I received a copy of this book from the author in exchange for an honest review.

—–

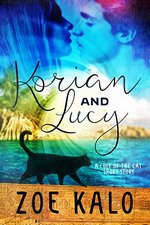

Korian and Lucy

Korian and Lucy