I was pretty excited when I got the email for this excerpt, it was precisely what I’d hoped Marks would give me (and a little more, but that’s just frosting on the cake). This is a great sample of the book.

From author Paul D. Marks: Bobby Saxon’s on a mission. He wants to play piano for the Booker ‘Boom-Boom’ Taylor Orchestra (big band), the house band at the famous Club Alabam on Central Avenue in the heart of Los Angeles during World War II. But there’s a problem: he’s young and he’s white. So if he gets the gig he’d be the only white player in the otherwise all-black band. That’s not the only thing standing in his way. In order to get the gig he must first solve a murder that one of the band members has been accused of. And if that’s still not enough there’s another big thing standing in his way…

This excerpt begins the morning after the murder of Hans Dietrich aboard the gambling ship Apollo offshore from Los Angeles. Bobby had just played his first gig with the Booker ‘Boom Boom’ Taylor Orchestra on the ship and the band’s sax player James Christmas has been arrested for Dietrich’s murder. Booker shows up at Bobby’s apartment and asks Bobby to try to clear James of the murder. He figures since Bobby is white he can go places and ask questions that Booker can’t. And he makes Bobby an offer he can’t refuse…a permanent place in the band if he agrees to help.

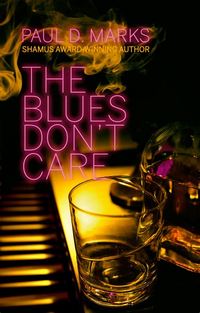

from Chapter Four of The Blues Don’t Care by Paul D. Marks (available from Down & Out Books)

Bobby’s head swirled with thoughts of James and the dead guy, Dietrich. Had James done it? Bobby didn’t know him very well but James seemed like a hot head. The way he overreacted to everything and seemed angry all the time, Bobby wouldn’t put it past him, especially since the dead German had made comments about colored people.

His wristwatch read five to twelve, almost the witching hour, but not very late by musicians’ standards, when he pulled up in front of his apartment in his 1935 Oldsmobile Six convertible. Several years old, it had been in an accident, so Bobby got it cheap. It was still one snazzy car and he loved the running boards, rag top, rumble seat, and magenta color. Not the original color, but a hot jazz color if ever there was.

Bobby grabbed his stuff, didn’t bother locking the car, headed up the walk. His building was like a thousand others in Hollywood, a million in L.A. White stucco and Spanish style, but it had seen better days. He opened the wood-and-glass-paneled front door, walked down the carpeted but threadbare hall to his tiny apartment in the back. He’d thought about going to a Gene Autry Western at the all-night theater to unwind, decided against it. A smoke and his couch would help him unwind just fine.

He threw off his hat and coat, yanked off his tie and shoes, and flopped on the sofa. It was too much trouble pulling down the Murphy bed. He pulled out the ever-present pack of Viceroys, lit up, drew hard, turned on the radio—war news, what else? It was as good as anything to drift off to sleep to.

Intense morning sun streamed through the venetian blinds, casting long shadows, while dust mites jitterbugged on the light. Bobby, asleep in his clothes on the couch, turned. A loud knock on the front door seeped into his semi-consciousness. Who the hell was it, the cops?

He got up, adjusted his shirt carefully, making sure everything was in place. He ran his hand over his chin and cheek, then headed to the door, saw Booker through the peephole. Booker was in the same suit he’d worn last night; looked like he’d slept in it.

“Booker,” he said, opening the door.

Booker stumbled in. “You got any coffee?”

“Sure.” Bobby walked to the kitchen on the far side of the room, followed by Booker. He started the percolator while Booker made himself comfortable at the banquette. “How ’bout some breakfast?”

“I didn’t sleep at all, Bobby. You?”

“Nothing keeps me from sleeping.”

“You’re lucky.”

“In some ways.” Bobby thought this was a slip, but Booker didn’t pick up on it. Bobby started frying up some eggs and bacon. Making toast. They would use up most of his rations for the week, but Booker was a guest.

“I got a funny look from one-a your neighbors coming here.”

“Probably Mrs. Hazelton, the landlady.”

“I don’t think she likes colored folk in her neighborhood.”

“She looks at everyone like that. I’ve been living here a year and she still looks at me funny.”

“I don’t know if you’re telling me the truth or not, but it makes me feel better anyways. Bobby, this is a nice place.”

“This dump? It’s all right, but I’m aiming to move to better digs.”

“You ain’t no rich white boy just slumming, playin’ on Central Avenue with the darkies to stick it to your folks?”

“Nope.”

“You go to school?”

“I graduated high school. I like to read. But I’ve never been to college.”

“That’s good. I don’t want no eggheads in my band. They tend to intellectualize everything.” Booker sipped the coffee Bobby gave him. He looked the room over. “So, where’s your piano?”

“If there was a piano in here there’d be no room for me. I go to my old piano teacher’s house in Edendale to practice.”

“Edendale? The land of kooks and crazies.”

“Maybe that’s why I fit in.” Booker laughed. “So who do you like? Musically.”

“Benny Goodman. Dorsey. Ellington. Armstrong.” “All the usual suspects.” Booker threw a hard glance at Bobby. “So whatd’d ya think about them hauling James off?”

Booker’s abrupt change of subject threw Bobby for a moment as he put out the plates of food and topped off Booker’s coffee. He set a bottle of ketchup on the table. Both of them dug in. Anyone looking at this scene from outside would have seen two pals chowing down.

“Do you think he did it?”

“I don’t know, man,” Booker said. “What I do know is that the cops don’t care. They got a suspect. A colored suspect. They’re happy. I know you and James aren’t exactly tight, but maybe you can do some checking around.”

“What do you mean?”

“You know, ask some questions. See what you can find out.”

“Criminy, Booker, I’m no detective.”

“I know that. But you got something I don’t, something no one else in the band has.”

“What’s that?”

“A passport.”

“Passport?” Booker pinched Bobby’s pink cheek. “White skin. You can go places we can’t. Ask questions we can’t and get away with it. Maybe even get some answers.”

“You want me to play Sam Spade? Like in that movie The Maltese Falcon?”

“Sure, why not? But you ain’t no ‘spade’ far as I can see.” Booker looked Bobby up and down, grinned.

“I’m no Humphrey Bogart either.”

“Hell no, you’re ten times better looking.”

“I’m not sure how much that says about me,” Bobby said. “But I do have a fedora. What else is there?”

“A gun.”

“Well, that I don’t have.”

“And hopefully you won’t need one.”

Bobby hoped not. He had never fired a gun, though he’d seen Gene Autry and Roy Rogers and Bogart all do it in the movies a million times. What was he getting himself into?

“What about the gig, I’ll have to be there every night to play.”

“There is no gig. The Apollo’s shut down, at least temporarily. And you’re on probation with the band. You solve this, you got the gig.”

“I thought I’d get the gig ’cause I can play.”

“That too. ’Sides, what else you got to do now that we’re on hiatus since they shut the Apollo down?” Booker shrugged. “If you get James off, I’ll give you a permanent spot with the band.”

“What if he’s guilty?”

“If he is, if you prove him innocent or guilty without a doubt either way, you got the gig.”

“So where do I start?”

“You seemed to be talking to that plainclothes deputy a long time. Maybe start with him. See what they have on James. I’m gonna try and get him a lawyer. White lawyer. Jewish lawyer.” Booker took a drag on his cig.

“I want a spot, but I want it ’cause I’m a good musician.” “You are a good musician. Now go and be a good detective.” Bobby had no idea where to begin, but something inside him liked the idea of playing detective, at least for a little while, even if he wouldn’t admit it to Booker. It might make him more of a man.

Bobby parked across the street from the Los Angeles County Hall of Justice, an imposing building and right now it was imposing itself on Bobby. The top five floors of the 1926 beaux arts structure housed the main jail for the county and that’s where Bobby was headed. He stood in its shadow, trying without success to light a cigarette in the wind. He stopped, looked at the columns of highly polished gray granite, tossed his match. Headed inside.

Ionic columns, marble walls, a gilded ceiling, and a vaulted foyer, looking like a Grecian palace and running the length of the building, belied the jail that lay on the top floors. All that majesty changed when Bobby got off the elevator on the fifth floor. The unwelcoming yellowed linoleum and hard-tiled walls made Bobby’s footsteps carom off the ceiling. The visitor’s area, with its filtered yellow light and stained dull green walls, didn’t improve his mood. And if this is what the county presented to the public, he couldn’t imagine what the jail’s cells were like. He longed for a drag on a cigarette.

A uniformed deputy sat him at a long wooden table. The scarred surface bore the marks of almost every prisoner who’d sat there. A large, pissed-off-looking man shuffled in, accompanied by a larger, more pissed-off deputy.

“Yer the last person I expected to see here,” James said, looking even angrier upon seeing Bobby.

“Booker asked me to come.”

“’Course you wouldn’t come on your own.”

Why the hell would I the way you went after me? “Do you hate everyone or just whites?”

“Mostly whites. But I pretty much hate everyone equally.”

“I think you hate yourself more than anyone else.”

Instead of shutting James up, he came back with, “Don’t go being no Freud on me. Why don’t you go home to your silver spoon and perfect family?”

Bobby stifled a laugh. “Booker asked me to help you.”

“An’ what can you do for me, white boy? You who’s wet behind the ears and don’t even look like you started shaving yet.”

“I see that you don’t need my help. Enjoy the food, I hear it’s yummy in here.” Bobby got up to leave, turned his back on James.

“Bobby?” James stood. The deputy shoved him down on the chair—hard. “Wait.”

They stared at each other across the table. The deputy stood rock solid behind James. The look in his eyes said he hoped the big man would make a move. James disappointed him. In a very small voice that admitted defeat, he said, “Got a smoke?”

Was that James’ way of asking Bobby to stay, maybe even to help? Bobby shook out a Viceroy, started to pass it across the table. The deputy took it, rolled it around in his fingers, probably to make sure a Bowie knife wasn’t hidden inside, and handed what was left of the crumpled cigarette to James. He put it in his mouth and Bobby lit it for him.

“Maybe I do have a small chip on my shoulder.”

Bobby sat down again. “I’ll say. Only about as small as the Rock of Gibraltar.”

“Well, could be bigger. Could be as big as Everest.” James cracked the slightest smile, held up his arm. A long, angry slash. Fresh. He pulled up his shirt. More bruises. The deputy slapped his billy club on James’ shoulder. The shirt went down.

“What happened?”

James leaned in, talked softly, “They beat me. Of course, they kept away from my face. But they had a hell of a good time doin’ it. And my chip keeps growing. So what’d Booker send you here for? Got a hack saw up your sleeve?”

“He thought I might be able to help.”

“You got friends or maybe your daddy’s on the po-lice force?”

“No. But why don’t you tell me where you were when Dietrich was killed.”

“That his name? No one ever told me.” He sighed. “’Course no one knows exactly when he was killed. But they had to have enough time to haul the body up to the rafters. I think I was probably back in the lifeboat, smoking reefer. Wasn’t feeling too good that night. Seasick, you know. And mad as hell after my confrontation with this Dietrich.”

“Uh,” Bobby didn’t know how to proceed. He was no private eye. “Was anyone with you?”

“I know I’m just a lowly spade, but I don’t have to have someone holding my hand every minute.” “I’m trying to help. It would be good if we had someone to alibi you.” Bobby was getting into the rhythm of being a detective.

“Got no alibis. All I got is my sax and I don’t even have that here.”

“And we miss it in the band.” Bobby stared beyond James, at the grimy walls. “James, did you do it?”

“Hell no!”

Bobby figured people in jail lied. He didn’t know if James was lying or not. But for now he’d take him at his word. “I’ll do what I can.”

He pulled out his pack of Viceroys, tossed it on the table. The deputy grabbed it. Stuck his fingers inside, pulled two cigs, tossed them to James. Stuck the pack in his pocket.

Out on the street in front of the jail, Bobby sucked in a deep breath of fresh air, opened a new pack of smokes. Lit up and took one long drag. He looked across the road to the rundown Bijou Theatre, playing a re-release of The Maltese Falcon. Bobby darted across the street. Short of a correspondence course on private detecting, he figured this would be about as much of a class in the subject as he could hope for.

Bobby emerged from the theater a couple hours later to a dark Los Angeles, lit by streetlamps haloing in the low-hanging fog that had rolled in. He got in the Olds, cut over to Beverly Boulevard, drove west. I should be playing music, not hunting for a killer. I didn’t take a correspondence course in Detecting 101. Criminy, I’m even more of a fish out of water than Booker knows.

Where the hell do I go now? I guess it would help to know who the, uh, dead guy is, was. I have to look at this logically, Bobby thought on the drive home. The answer’s probably right in front of my face.

He flopped on his sofa, listening to Artie Shaw’s sweet clarinet on the radio in between war news. Bobby flipped through the pages of his high school yearbook. He had tried calling Deputy Nicolai. He had gone home for the day. The desk sergeant wanted to take a message. Bobby didn’t leave one.

The Andrews Sisters’ “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy” followed Shaw. Bobby’s eyes grew moist. All those boys overseas. The service flags in almost every window, gold star flags in too many of them. Sometimes he wished he could join the boys in Europe or the Pacific. He didn’t want to think about that now. He wanted to look at the pictures in the yearbook. Johnny Larkman, senior class president. Very handsome. Is that why he was prez? Jane Feldman, most likely to succeed. What else could she be with her glasses and librarian hair? David Chambers. Handsome, smart. The reason Bobby had pulled out the dusty old yearbook in the first place. David in drama club with Bobby. They had appeared in Cyrano de Bergerac together. In the lead roles. Georgiana Greene, voted prettiest and homecoming queen. Bobby had had a major crush on her. Who didn’t? Mary Cooper. Bobby’d sent her a love note in fifth grade and gotten in trouble for it. Mary never said another word to him. They all went through school together, elementary, junior high, high school. And now they were all out on their own, facing their demons. Facing the world. He kept turning pages and reliving memories. Band. Drama club. Lunches in the quad.

It was fun seeing David Chambers the other night, even if Bobby had been too shy to go up to him. He must be doing pretty good to have money to spend on the Apollo.

Bobby fell asleep on the sofa again.

The Malibu sheriff’s outpost, or station, wasn’t much to look at. At least parking was easy. Bobby got out of the Olds Six, inhaled fresh ocean air. Walked inside. After some palavering with the desk sergeant he was allowed back to the detective room. It looked a lot like detective rooms in the movies did. A bunch of wood desks with blotters, file cabinets, and telephones. Men in shirt sleeves and shoulder holsters, some with fedoras on their heads, some with their hats on their desks or hanging from a rack.

Bobby and Sergeant Nicolai sat at a desk in the corner, by the water cooler. Bobby explained he’d come to find out what he could about the Dietrich case.

“Why’re you so interested?”

“James is a member of the band. I’m a member of the band.”

“Doesn’t sound right. Gotta be something more.”

“We have no gig. The Apollo is shut down. We need to hold the band together,” Bobby vamped.

“With a murderer?”

“What if he isn’t?” Nicolai thought a moment. “I’d like to help you but I can’t divulge information on an ongoing investigation.”

“Is it ongoing, Sergeant? And that sounds like a very nice, very formal ‘don’t bother me, kid.’ ”

“I don’t buy your spiel. That boy a friend of yours?”

“I’d hardly say that. But he is a bandmate and we need our first sax.”

“So why doesn’t your leader, Mr. Booker Boom-Boom, come down here himself?”

Bobby’s eyes wandered the room. Nicolai followed. He knew the answer.

“All right, I know why he doesn’t come down. Still—”

“Can’t you give me something?”

“His name’s Hans. Hans Dietrich. I believe he worked in the import-export field. That’s all I know.”

Bobby looked down, then up and straight into Nicolai’s eyes. “I got that much from the papers.”

“You’re a persistent little cuss, aren’t you?” “I got Booker to give me a spot in the band.” “And now you think I’ll just give you information in an ongoing—”

“Tell me something I don’t know and I’ll get out of your hair.”

“Something tells me you’ll never be out of my hair.” Nicolai drew a deep breath. “He and his partner, Harlan Thomas, an American, worked as Dietrich Enterprises, on Third Street. Dietrich’s a German citizen, moved here a couple years ago. Forty-five. Unmarried. Blonde over blue. No arrests.”

“That should get me started. Thanks, Sergeant.” Bobby stood, tipping his hat to Nicolai.

Bobby lit up a Viceroy, stepped out into the raging sun and wind and fresh, stinging ocean scent.

“So who are you,” Bobby sucked in the cigarette, exhaled, “Mr. Hans Dietrich?”

Excerpted from THE BLUES DON’T CARE Copyright © 2020 by Paul D. Marks. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

Thanks to Down & Out Books, Paul D. Marks and Saichek Publicity for this excerpt!

![]()