Like every single year, I didn’t read as much Non-Fiction as I meant to — but I did read a decent amount, more than I did in 2016-17 combined (he reports with only a hint of defensiveness). These are the best of the bunch.

(in alphabetical order by author)

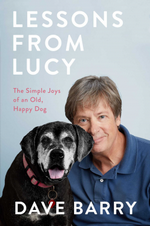

Lessons From Lucy: The Simple Joys of an Old, Happy Dog

Lessons From Lucy: The Simple Joys of an Old, Happy Dog

by Dave Barry

My original post

So, I figured given the tile and subject that this would be a heavier Dave Barry read, with probably more tears than you anticipate from his books — something along the lines of Marley & Me. I was (thankfully) wrong. It’s sort of self-helpy. It’s a little overly sentimental. I really don’t know if this is Barry’s best — but it’s up there. Lessons From Lucy is, without a doubt, his most mature, thoughtful and touching work (that’s a pretty low bar, I realize — a bar he’s worked hard to keep low, too).

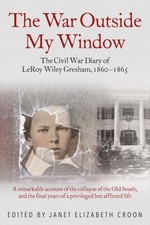

The War Outside My Window: The Civil War Diary of LeRoy Wiley Gresham, 1860-1865

The War Outside My Window: The Civil War Diary of LeRoy Wiley Gresham, 1860-1865

by Janet E. Croon, ed.

My original post

LeRoy Wiley Gresham was 12 when he started keeping a diary. LIttle did he know at that point that he was about to witness the American Civil War (and all the desolation it would bring to Georgia) and that he was dying (he really didn’t figure that out until the very end). Instead you get an almost day-by-day look at his life — what he does, reads, hears about (re: the War) and feels. It’s history in the raw. You have never read anything like this — it will appeal to the armchair historian in you (particularly if you’ve ever dabbled in being a Civil War buff); it’ll appeal to want an idea what everyday life was like 150 years ago; there’s a medical case study, too — this combination of themes is impossible to find anywhere else. This won’t be the easiest read you come across this year (whatever year it is that you come across it), but it’ll be one of the most compelling.

Timekeepers: How the World Became Obsessed With Time

Timekeepers: How the World Became Obsessed With Time

My original post

I, for one, have never thought that much about my relation to time, my relation to clocks/watches, etc. I know they govern our lives, to an extent that’s troublesome. But where did that come from, how did we get hooked on these things, this concept? These are brief studies/historical looks/contemporary observations — and I’m not selling it too well here (trying to keep it brief). It’s entertainingly written, informative, and thought-provoking. Garfield says this about it:

This is a book about our obsession with time and our desire to beat it. . . The book has but two simple intentions: to tell some illuminating stories, and to ask whether we have all gone completely nuts.

He fulfills his intended goals, making this well worth the read.

Everything is Normal: The Life and Times of a Soviet Kid

Everything is Normal: The Life and Times of a Soviet Kid

My original post

If you grew up in the 80s or earlier, you were fascinated by Soviet Russia. Period. They were our great potential enemy, and we knew almost nothing about them. And even what we did “know” wasn’t based on all that much. Well, Sergey Grechishkin’s book fixes that (and will help you remember just how much you used to be intrigued by “Evil Empire”). He tells how he grew up in Soviet Russia — just a typical kid in a typical family trying to get by. He tells this story with humor — subtle and overt. It’s a deceptively easy and fun read about some really dark circumstances.

Planet Funny: How Comedy Took Over Our Culture

Planet Funny: How Comedy Took Over Our Culture

by Ken Jennings

My original post

Half of this book is fantastic. The other half is … okay. It’ll make you laugh if nothing else. That might not be a good thing, if you take his point to heart. We’ve gotten to the point now in society that laughter beats honesty, jokes beat insight, and irony is more valued than thoughtful analysis. How did we get here, what does it mean, what do we do about it? The true value of the book may be what it makes you think about after you’re done.

The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good Life

The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good Life

by Mark Manson, Roger Wayne (Narrator)

My original post

This is an enjoyable, amusing, call to re-examine your priorities and goals. It’s not about ceasing to care about everything (not giving a f^ck), but about being careful what you care about (giving the right f*cks). Manson’s more impressed with himself than he should be, but he’s a clear and clever writer displaying a lot of common sense. Get the audiobook (I almost never say that) — the narration is worth a star by itself (maybe more).

Dear Mr Pop Star

Dear Mr Pop Star

My original post

If you read only one book off this list, it should probably be the next one. But if you pick this one, you’ll be happier. This is a collection of correspondence to pop musicians/lyricists picking apart the lyrics, quibbling over the concepts, and generally missing the point. Then we get to read the responses from the musician/act — some play with the joke, some beat it. Sometimes the Philpott portion of the exchange is better, frequently they’re the straight man to someone else. Even if you don’t know the song being discussed, there’s enough to enjoy. Probably one of my Top 3 of the year.

Them: Why We Hate Each Other – and How to Hea

Them: Why We Hate Each Other – and How to Hea

by Ben Sasse

My original post

My favorite US Senator tackles the questions of division in our country — and political divisions aren’t the most important, or even the root of the problem. Which is good, because while he might be my favorite, I’m not sure I’d agree with his political solutions. But his examination of the problems we all can see, we all can sense and we all end up exacerbating — and many of his solutions — will ring true. And even when you disagree with him, you’ll appreciate the effort and insight.

Honorable Mention:

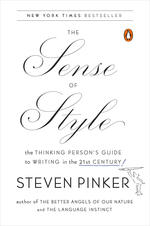

The Sense of Style: The Thinking Person’s Guide to Writing in the 21st Century

The Sense of Style: The Thinking Person’s Guide to Writing in the 21st Century

I started this at a bad time, just didn’t have the time to devote to it (and the library had a serious list waiting for it, so I couldn’t renew it. But what little I did read, I thoroughly enjoyed and profited from — am very sure it’d have made this post if I could’ve gotten through it. I need to make a point of returning to it.