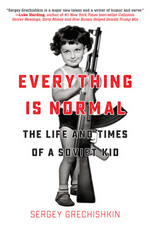

Everything is Normal: The Life and Times of a Soviet Kid

Everything is Normal: The Life and Times of a Soviet Kid

by Sergey Grechishkin

Kindle Edition, 336 pg.

Inkshares, 2018

Read: March 19 – 26, 2018

I would spend hours by the balcony window, watching smoke rise from the power station chimneys on the horizon and listening to the suburban trains chug by in the distance. Most of my memories of that time coalesce into a sense of timeless boredom. But after my first taste of bubble gum, something new began to mix with my malaise: jealousy of the kids in faraway countries who could chew such gum every day.

This is the kind of thing that you expect a memoir of growing up in the Soviet Union to be full of — a grim skyline, yearning for something unobtainable, a general malaise. But in Sergey Grechishkin’s book, you don’t get a lot of that — yes, it’s there, to be sure (how could it not be?), but there’s so much more.

Grechishkin writes with a vivacity, a thorough-going sense of humor, a spark of hope that you don’t expect — and are frequently surprised by. He doesn’t paint a rosy picture of the USSR in the 70s and 80s, but he paints a picture of a life with hope. The book focuses on his childhood — particularly school ages — we get a little before, we see him briefly in University, with a hint or two about what happens next. But primarily we’re looking at his time in school. This coincides with the time of Leonid Brezhnev (at least the tail end) through the early days of Mikhail Gorbachev, with all the changes those days entailed. It’s not an incredibly political book — but it’d be difficult to discuss life under these various leaders without mentioning them and the way each government was different from the previous.

A word about the humor — which is all over. We’re not talking Yakov Smirnoff, first off. Secondly we’re not talking about anything that makes light of the hardships, or denies them. But comments that can talk about the hardships in a way that is above to find the humor in the human condition or something else we can all relate to: like

So many Soviet friendships and even families have been formed while standing in lines.

Nothing major — just a quick smile as you read. At other times, he’ll deliver a hard truth about life in the USSR through a joke. Like here, when describing how they couldn’t process the appearance of Western athletes on TV during the 1980 Olympics criticizing their governments:

For those lucky Soviet citizens who were allowed to cross the border, any sort of misbehaving while abroad or giving the slightest hint at being unhappy with the Soviet workers’ paradise would mean no more trips anywhere except to camping locations in eastern Siberia.

You laugh, and then you realize that he’s talking about a harsh or sad reality while you’re laughing. I don’t know how many times I’d think about something being funny or actually be chuckling at something when I’d catch myself, because I realize what he’s actually getting at.

The jokes slow down as he ages and the narration becomes less universal and more particular to his life — looming chances of being sent to Afghanistan, and other harder realities of adulthood on the horizon. It’s still there, it’s just deployed less.

While narrating his life, Grechishkin is able to describe living conditions, schooling, medical care, shopping, food, friendships, family life, dating, Western movies, crime, the role of alcohol in society, political dissidents, and so much more. I enjoyed his discussing the experience of reading George Orwell (via photocopy) or listening to Western pop music — learning that LPs were “pressed at underground labs onto discarded plastic X-ray images.” You can do that? That sounds cool (and low-fidelity). Almost everything in the book seems just the way you’d expect it, if you stopped to think of it — but from Grechishkin’s life experience it seems more real.

This is one of those books that you want to keep talking and talking and talking about — but I can’t, nor should I. You need to read this for yourself. If only because Grechishkin can do a better job telling his story than I can. You really don’t think that this is the kind of book you can enjoy — but it is..

Did I have a happy childhood? Well, it was what it was. From a nutritional and a relationship standpoint, it wasn’t particularly great. But it also wasn’t awful or tragic. It was, when I look back on it now, normal.

Normal was a word that showed up more than once in my notes — despite everything around him, his childhood seemed normal (and its only now that I remember tat the word is in the title). I’m not saying that I’d trade places with him, his life was not easy — or that there weren’t kids in Leningrad who suffered more forms of deprivation or oppression (not to mention kids in less well-off areas in the USSR). But on the whole, he had a childhood thanks to a caring family, a good school, and good friends. Everything is Normal shows how against a bleak background, a normal life can be possible. It does so with heart, perspective, humor and a gift for story-telling. Exactly the kind of memoir that will stay with you long after you finish the book. Highly recommended.

Disclaimer: I received this book from Inkshares in exchange for this post and my honest opinion.

—–