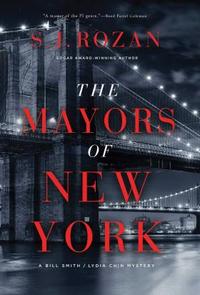

The Mayors of New York

The Mayors of New York

by S. J. Rozan

DETAILS: Series: Lydia Chin & Bill Smith, #15 Publisher: Pegasus Crime Publication Date: December 5, 2023 Format: Hardcover Length: 280 pg. Read Date: December 21-25, 2023

What’s The Mayors of New York About?

New York’s first female mayor has a problem. A few months after taking office, her fifteen-year-old son has run away. It’s not the first time, but it’s the first time since she’s been elected. She’s in the middle of high-stakes negotiations with a police union, so Mayor McCann doesn’t feel like she can turn to them without taking some PR hits/weakening in the negotiations.

So, she has her aide hire Bill Smith (who brings along Lydia, of course). It’s not easy tracking down one of the most recognizable teens in the city without letting anyone know you’re doing that—and it almost seems like the “without letting anyone know” part might overrule the “finding the teen” part of the job.

Now, Lydia’s trying to decide if she takes on a case of her own at the same time. Readers know long before they do that these cases will end up intertwined—otherwise, why would Rozan bring it up? And once Bill and Lydia cotton on to that, a hunt for a runaway takes on a whole new layer. Possibly several layers.

The Characters

Nah, I’m not going to talk about Bill and Lydia today—I honestly don’t know if I have anything else to say about them outside how they’re probably my favorite partnership in Crime Fiction (Robin/Cormoran—learn from these two. They trust each other and communicate frankly. Your lives will be the better for it, and the books will be shorter, too. Everyone wins.).

I want to talk about Mark McCann a little bit. At first, he’s just the target. He’s little more than a MacGuffin to get the plot moving. Then we start to learn a little about him and he becomes an actual character—one I want to learn more about. Then we get to meet him, and I like him a lot. And then Mark goes ahead and does some clever and stupid (read: dangerous) things and I want to see more of him.

The wanting to see more of him goes for everyone who’s alive and not under indictment of some sort at the end of the book—the McCann’s household staff, the people who help Mark along the way (and then help Bill and Lydia), and so on. I know it’s not really Rozan’s style, but if we could run across them in future books for a chapter or so just to spend more time with them, I’d really enjoy that. These all have a little more life to them than your typical witnesses, bystanders, and so on in PI Fiction. I particularly appreciated the way they all want some sort of Mayoral favor shown to their neighborhoods/communities and the way that Lydia takes notes to pass them along. A very nice—and real—note.

I feel like I should spend a few paragraphs on the most interesting character in this novel—Aubrey “Bree” Hamilton, the mayor’s aide who hires Bill to look for Mark. She and Bill dated years ago, and it’s clear from Bill’s First-Person Narration that the chip on his shoulder regarding this particular cheating %#&@ has is still pretty deep, no matter what degree of happiness he’s found elsewhere. It’s not just the way she cheated on him—Bill has no sympathy for her former PR clients (lawyers, largely) or the politicians she now works for, assuming everything they do or say is calculated for their benefit. He trusts Bree less than her bosses—and we see that throughout—but something about a 15-year-old boy who keeps running away from home speaks to Bill, so he has to investigate.

I got off target there, but I thought I’d explain Bill taking the case when he can’t stand anyone involved. Bree is a perfectly designed character—the reader can see how she’s good at her job, calculating, smart, and generally three steps ahead of anyone (aside from our protagonists occasionally). It’s impossible to tell how much she believes a lot of what she says, or if she’s saying it out of duty. And then there’s what she says to yank Bill’s chain a little bit. Bill (and therefore his narration) is so jaded against her that it’s hard for us to know how much of our negative reaction to her is justified and how much it is seeing her through Bill’s eyes. A great move by Rozan.

So, what did I think about The Mayors of New York?

The pace is fast without being breakneck. The dialogue is sharp and witty. Bill’s narration has never been more hard-boiled (his contempt for the client/client’s intermediary helps). The characters jump off the page. It’s what you want in a PI novel.

Early on, I had inklings about what was behind everything (and I’m pretty sure Rozan intended readers to). As the plot moved forward and we received more and more confirmation about those inklings, it made me uncomfortable and a little queasy. Why couldn’t I have been wrong? Why couldn’t these have been red herrings? Thanks to some skillful storytelling you don’t get bogged down in the wrongness of everything that’s afoot—it’s there and it colors everything, but your focus becomes on the characters dealing with it all, the reveals to other characters and the nail-biting way this story is resolved.

Yes, I think Rozan could’ve just as easily and skillfully let the characters and readers wallow in the muck of the crimes behind everything—but it would’ve changed the tenor of the book so much that the early chapters would feel out of place, and we probably wouldn’t have found some resolution that’s as satisfying.

Also, just because some things weren’t red herrings, don’t think that Rozan doesn’t toss enough of them at the reader to keep you wondering.

Rozan has been on a hot streak since Paper Son, and The Mayors of New York shows no signs of her slowing down anytime soon. And I am more than okay with that. If you’ve never indulged in this series before—this would work as a jumping-on point. Almost any of them would, really. The trick is to jump on somewhere for some of the best that PI fiction has to offer. A touch of the classic American PI added to a hefty helping of the 21st century. The Mayors of New York is one I heartily recommend to all.

This post contains an affiliate link. If you purchase from it, I will get a small commission at no additional cost to you. As always, the opinions expressed are my own.

![]()